“People help you, or you help them, and when we offer and receive help, we take in each other.

And then we are saved.” – Anne Lamott

I sat alone in my car at a red light on a busy east side street a few weeks ago.

Feeling tired, I dropped my face into my hands and rested there for several seconds. When I looked back up, there was still a red light and a minivan next to me with a man with a blonde combover in the driver’s seat. He was aggressively waving his arms at me.

When he saw he had my attention, he mouthed the words “Are you okay?” with a point of his index finger and the universal OK sign, followed with a big mime-like raise of his eyebrows.

I think I looked at him dully for about a second before smiling a little and nodding in a way that was probably also more Marcel Marceau than natural human. I might have even given him a thumbs-up sign. As he nodded back, smiled and pulled away, I felt strangely grateful for his concern. His out-of-nowhere, stoplight, blue minivan concern for some woman in an old Toyota resting her face in her hands.

The last three years have taught me more than I ever expected to know about the kindness of strangers — not to mention other people I might have been acquainted with, but had no way of knowing I could trust. At some point, when things were oppressively difficult in my life, I just started answering the question “how are you?” honestly all the time. I was not okay. I was hanging out with death and deadly illnesses and divorce and the effects of others’ addictions while trying my best to be a halfway decent mom.

But when I told people some piece of that information, I was amazed to find that I wasn’t exposed or embarrassed or humiliated. I was helped and encouraged. They held up a mirror and let me know that I didn’t appear to be as wounded as I felt. They told me I was a good mother or a good person. They rose to meet my honesty with their own. Sometimes they told me things that were braver than I ever imagined, making my own truths less scary and alien. I was saved. Over and over, I was given faith and hope in the primordial goodness of people.

As I made my way home from the minivan man, I drove past the Grill and Skillet – the dictionary definition of a greasy spoon. And I remembered another time in the spring of 2010, when someone asked me if I was okay on a day when I definitely was not.

“Let me take you for a coffee,” she said.

She was a woman of few means, but she was wealthy and generous with wisdom, and she liked to make a big production of treating people to the delights she could afford. She bought me that coffee and some toast at the Grill & Skillet, while she munched on four pieces of bacon.

“I’m skipping all the ordinary calories and just going straight for the devil today,” she told me. Then, eyeballing my jailhouse snack, “You’re a cheap date. Are you sure you don’t want anything else?”

All I genuinely wanted was some of peacefulness she seemed to possess, her natural ability to be true to herself. I don’t remember what her exact words were to me that day, but if I had to venture a guess, it was probably something like “you need to think about acceptance, baby, about accepting things as they are. It will free you.”

Every time I spent a few moments with her, I could feel a deep turning in my life, away from self-created obstacles and emotional storms.

And I remember watching her, usually moving slowly because of a tumor in her leg, dragging a heavy, quilted bag of self-help and meditation books and paper worksheets on things like identifying emotions that she felt would be useful to others. If you were in need, she would probably make you wait a little while. She might have to take care of something for herself first, like getting a drink of water or a snack – often something that seemed quite trivial compared to the desperately catastrophic things you were feeling. But then she would turn towards you, become present with you, and you were enveloped in the safety of her wisdom, usually ending with a hug that was equally, spectacularly enveloping. There was no telling whether you would be lifted for moments or days – that would depend on you – but you would be lifted.

Best of all, you would witness the grace she received for herself by helping you. As she sensed you lightening, she would lean back and smile. “I have an affinity for people like you,” she would say. “We have experienced the same kinds of pain, so know that I mean it when I tell you that I love you and I love to be of service to you.”

You were not a burden. Your willingness to share and trust actually gave her something too. Not only had you unburdened yourself to someone safe, you had been useful to that person.

After the Newtown killings and the apocalypse that wasn’t, Facebook, my email, phone calls and friends on the street have made me feel like we’re becoming a nation of blue minivan combover men and toast-buying women. “Are you okay?” we ask each other in the wake of fallen children, heroic educators and jokes about the world’s demise. Because no matter how much news fasting, meditation or other exercise in equanimity that you practice, there’s little or no getting around feeling a tragedy like this one, feeling the insanity of any human being treating the world like there is no tomorrow.

I keep returning to the notion that we are never as helpless as we think. Two weekends ago, I heard a wise teacher say “Love and compassion are never in vain. They are never useless. They are never powerless.”

And that’s the lesson from my friend that has remained with me most powerfully, a year and a half after her passing. (The lesson that the minivan man and a drive down Main Street brought back to my attention.) She showed me that when you take good, consistent care of yourself, helping or caring for others is not only not a burden, it’s a blessing. You take that sip of water first. You say “I’ll call you back after I take a nap.” You eat a sandwich. You swim or meditate or pray or spend time petting your dog. You do what it takes to make sure your center is as strong and balanced as it can be today.

Then you walk toward that next person you see hurting, preferably without any expectation that they are even ready or willing to accept anything you have to offer.

“What can I do to help you?” you ask.

If the answer is “nothing,” you accept that.

If the answer is something you consider, then realize that you can’t give them, you tell them that directly.

But there is often something you can do. Sometimes just the question “what can I do to help you?” is a greater gift than you might imagine. It may be days, weeks or years before you realize that you actually helped someone. You may never know you helped them.

You do it anyway. And you are saved.

Last night on the freeway I came upon an accident that I must have missed witnessing by less than a minute. The white SUV, flipped on its side on the side of the road, had twisted metal everywhere. Its lights were still on and I could see the silhouettes of two people, still hanging in their seats. I did not let my gaze rest there, having that sick, gut feeling that I was in the presence of lives, if not at that instant lost, permanently altered.

Last night on the freeway I came upon an accident that I must have missed witnessing by less than a minute. The white SUV, flipped on its side on the side of the road, had twisted metal everywhere. Its lights were still on and I could see the silhouettes of two people, still hanging in their seats. I did not let my gaze rest there, having that sick, gut feeling that I was in the presence of lives, if not at that instant lost, permanently altered.

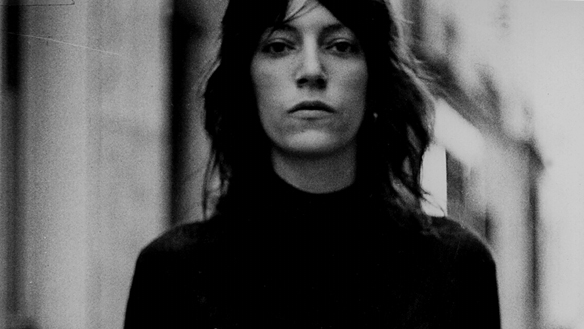

At the beginning of the year, I made the aspiration to read fewer Buddhist and self-help books. I bought and started Just Kids by Patti Smith, but I didn’t get very far. Life-changing things just kept happening. I needed my little daily meditations and other methods of head-clearing. I lacked the focus for much else. So I decided to wait on the story of Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe until I could give it my full attention.

At the beginning of the year, I made the aspiration to read fewer Buddhist and self-help books. I bought and started Just Kids by Patti Smith, but I didn’t get very far. Life-changing things just kept happening. I needed my little daily meditations and other methods of head-clearing. I lacked the focus for much else. So I decided to wait on the story of Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe until I could give it my full attention.