Good morning dearest boy,

Good morning dearest boy,

For the past twelve months, things have gone something like this:

Me: “Wow, you are going to be a teenager in X months,” or “Can you believe you will be a teenager on your next birthday?”

You: “Noooooooooooooooooooooooooo!” (Quickly covering face with hands, blankets, a beagle, book, or whatever else is handy.)

I think this is a completely appropriate response to the prospect of growing up. Larry and I do what we can to cushion the blow, perpetually making up songs with lyrics such as, “darkening arm hair means you’re a man” or “peculiar emotional responses mean you are becoming a man” or “mind-numbing standardized testing that’s created by politicians and used to judge teachers rather than assess your knowledge in any meaningful way makes you a man…”

So here we are, finally arriving at the doorstep of the dreaded baker’s dozen. It’s prime. It’s a Fibonacci number. It’s even an emrip, which I didn’t know was a thing, but is apparently a prime number that results in a different prime number when its decimal digits are reversed. It’s also a “happy number,” which I also didn’t know was a thing, but I think it’s best to take that one at face value. I consider it a lucky number. The first time I met Larry in person, we spent an entire Friday the 13th in Cincinnati, looking at contemporary art and century-old architecture. I’ve looked forward to every Friday the 13th ever since, because I associate it with hope and love and new beginnings, not Jason Vorheese or scary ree ree ree sound effects.

You took off into 12 running. Literally. You joined the cross country team and got up early on summer mornings to move your body for weeks before the school year started. This wasn’t easy for you at all, but you were so determined. You finished every race, no matter where you were compared with the pack. You showed so much heart. You showed us a form of endurance that lives well outside of winning. By the end of the season, another mom even told me that you inspired her to start running again. She wanted you to know this.

Right as you started your first year of a traditional middle school, I pulled you out for a couple of days so we could travel to see the solar eclipse in totality. We landed in Hopkinsville, Kentucky, at a Trail of Tears park where Cherokee chiefs were buried. With the apparent successor of Andrew Jackson sitting in the White House, it felt like the most tender place on the planet where we could stand and watch the cosmos show us who the boss really is. I took pictures of you surrounded by crescent shadows before you began narrating the scientific phenomena of every step of the event. The animals went quiet and everything grew dark. People all around us began bellowing. Just… yelling. So did I. Larry and I cried as though we’d seen through to the other side of the veil. Once again, I felt so lucky to be your mom. Helping you follow your passions has given me uthe gift of the universe so many times over. Would I have ever made that 6-hour trip if not for you? I doubt it. I learned that there are people who travel to the far reaches of the world for any chance to witness solar eclipse totality and oh my goodness, now I understand why. Thank you, my sweet boy. Thank you.

Your cousin Lily once said these words to me: “Seventh grade is a dark time.” I immediately felt that this was one of the truest things that I’d ever heard. The sharp bells and harshly lit hallways of your new school boiled all of my own junior high anxiety up to the surface. I remember the math teacher who thought public humiliation was a solid teaching strategy. I remember the day when I dressed up sharp and got a half-dozen compliments from teachers and others as I walked into the building, but when the girl at the locker next to mine said “you look like an A**Hole,” to my happy face, it bored into me for months. (Or years, I guess. Gee whiz.) My own projections and anxieties and expert catastrophizing might have been the hardest part of your adjustment, because, even when you’ve had disappointing or flailing moments, you don’t seem to carry them like I did. Or it might be that you are protecting me from them. I don’t know. I hope you tell me when you’re 30. One truth of middle school, just like the rest of life, might be that often everything is just fine until it isn’t.

We went to a party with Larry’s colleagues last fall and I heard  someone ask you how you liked middle school. “I’m not a big fan of factory-model education,” you responded. Right on, man. And you know if I could take you to Finland or even to the Richard Feynman school in Maryland you know I would. (A school devoted to the sheer pleasure of learning – can you imagine that?) But the love happens to be where we live right now.

someone ask you how you liked middle school. “I’m not a big fan of factory-model education,” you responded. Right on, man. And you know if I could take you to Finland or even to the Richard Feynman school in Maryland you know I would. (A school devoted to the sheer pleasure of learning – can you imagine that?) But the love happens to be where we live right now.

Flat-Earthers and climate change deniers really get under your skin. You want there to be a world with free fresh air and potable water when you grow up (as do I) and you understand the risky place we are in. I admire the way that you still connect with people whose worldviews differ from your own, like your bus driver, Bobby. When he came back from a hunting vacation, he told you that he never kills anything for sport – only for food. Living in a Buddhist house where we catch and release any bug or critter we find, you admired this about him. He makes you laugh. You like this man and you trust him. I’m glad he is there, helping you feel safe on that sometimes cold and bumpy bus ride.

You are taking Spanish and want to become fluent… to “be able to think in another language,” you told me. One of the owners of a local Mexican eatery recognizes you whenever we walk in. You smile at each other and she encourages you to engage in small talk, so patient with the fact that you are learning. And the food is good!

One day last August, you came home and excitedly described the way the eighth grade band students looked as though their instruments closely matched their personalities. You were excited for the instrument fitting, sure that it was going to reveal something about you, like Olivander’s Wand Shop in Harry Potter. I never would have predicted that the euphonium would be the one to pick you, but it did. You’ve loved it and nurtured it, playing it and the piano back to back. You began to teach yourself classical guitar as well after receiving the instrument from your Giga and Uncle Steve for Christmas.

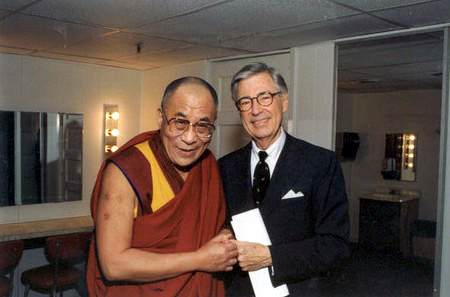

In social studies, you were taken with Gandhi and the history of nonviolent protest. We were sitting together at the kitchen table one evening when you talked about the way that Gandhi forgave his assassin as he died. You were so moved by the thought of this that you could barely speak and tears filled your eyes. I wanted to squeeze you and your tender, open heart forever, my sweet Karma Sherab Palzang.

You have also watched endless YouTube videos of Shiba Inu howls edited to the tune of “Take On Me” by A-Ha, cracked up at dark, weird Spongebob Squarepants parodies and frequently yelled “somebody touch-a mah SPAGHET!” back and forth with Larry across the house (the meme comes from a 1939 cartoon). You also sing Yoda’s “Seagulls: Stop It Now,” from Bad Lip Reading together a lot. I’m ever amazed that so many songs that were huge when I was around your age (“Never Gonna Give You up,” “Careless Whisper,” “Don’t Stop Believin’”) have been burned into your consciousness by way of comic/ironic YouTube reinventions.

You remain an epic snuggler of humans and canines, especially Walter, your “soul beagle,” although Leelu seems to be your true protector when you aren’t feeling well. You are also an epic juggler – you taught yourself this spring. It reminded me so much of you when you were a baby – so determined to form a new skill that I’d catch you practicing it in your sleep. Then as now, once you formed the revelation that you could do something new in your mind, you’d do it, often in a matter of hours. You’d be sitting up, crawling or cruising as though you’d been doing it forever. So it has gone with juggling. You walk into other people’s homes and ask “hey – do you have anything that I can juggle?”

At church, you grew into belonging with another new group of friends. Together you looked at social justice issues as Harry Potter horcruxes that you could defeat. You made welcome baskets for people who had been homeless and just gotten into housing. You threw a big, magical dinner to raise funds for food insecure children. You are winding up the year with a book drive for prison libraries.

As I sit here looking at this long list of things you have done during your 13th revolution around the sun, I am struck by how little of it has been my idea. I ask you how much you want my help keeping you organized in this busy, busy life you have. And you would still do more if I could find the resources to help you. You miss knitting. You like riding your bike around the neighborhood. You were singing at the salad bar at a restaurant, prompting a man to walk up to me and implore me to get my daughter some voice lessons. You told me you were glad that I didn’t correct him about your gender, and that yes, you’d love to take voice lessons if you somehow could – if we had time and money.

You still dance, and I’m so glad. The Lyrical class that you take seems to make you feel good in way that is about nourishment, not the hungry ghost that “achievement” can become. Learning is still one of the most fun things to you. I sometimes wish our new town and your new school didn’t feel so competition-driven. Let’s blame Bobby Knight and resist the urge to succumb to unreasonable external expectations and self-flagellation whenever we can. I still think that you win when you grow, feel elation or awe, express yourself, or connect with others. There’s no way to keep score of them, but I believe that these intangibles really need a cheering section nowadays. Let’s make up some chants and dance routines for compassion and nonsequitur humor and fascinating or beautiful things that make us pull in our breath and exhale a wow.

I t’s not a wonder that 13 is daunting when there is so much more that you want to do and explore. You are already running into new pressures that require you to make increasingly harder choices about which thing you can do or learn. But we’ll all keep breathing, sweet boy, even me. We’ll try to hold space for knitting and ‘80s memes and singing and juggling and snuggling and dystopian teen fiction and Steven Universe and bike rides and our fundamental belief in the basic goodness of all beings.

t’s not a wonder that 13 is daunting when there is so much more that you want to do and explore. You are already running into new pressures that require you to make increasingly harder choices about which thing you can do or learn. But we’ll all keep breathing, sweet boy, even me. We’ll try to hold space for knitting and ‘80s memes and singing and juggling and snuggling and dystopian teen fiction and Steven Universe and bike rides and our fundamental belief in the basic goodness of all beings.

I love being your mom, your friend and a witness to your life.

I love you infinity,

Mom

P.S. And if the homework brings you down, we’ll throw it on the fire and take the car downtown. – David Bowie, “Kooks”