(Image: A sculptural representation of Milarepa).

(Image: A sculptural representation of Milarepa).

When Declan was about four months old, I took a rare evening to myself so I could attend a teaching by Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso Rinpoche. It was to be, I believed, a dharma talk for Buddhist novices like myself, replete with a tantalizing title about the “purity” of desire, stupidity and anger.

After the Rinpoche and his translator entered the room and took their place in front of the group, they compelled us to sing. We sang a verse about the purity and oneness of desire and forms, followed by the same verse, only this time about the purity and oneness of desire and feelings, then about desire and discriminations.

For the first five rounds or so, it felt novel and fun. I sat with friends who brought their weeks-old baby girl, singing along cheerfully, confident that this was an overture for an illuminating lecture. But as we kept on going past four to five, six and seven verses, my friends and I looked at each other, and at the list of 100-plus virtues, vices, senses, feelings, elements and emptinesses that we were marching through.

“We aren’t going to sing all of these are we?” One of us whispered. There were shrugs all around. I started to feel vaguely annoyed. I wondered if I had chosen to spend my precious evening alone for nothing more than an extended Buddhist version of “99 Bottles of Beer on the Wall”?

But as a few more verses came and went, I resigned myself to this fate. Singing these lines would have to be my lesson. Once I accepted that, I enjoyed it immensely, the way that I had found that breathing and accepting the requirement to be still often made breastfeeding a time for meditation, rather than a struggle.

Somewhere during those verses, I let go of some of the noise in my head. I let go of some of the new, protective anger that motherhood had brought me, and the unfamiliar fears. After more than an hour of singing 60-plus verses, I did get the dharma talk that I had hoped for.

Now, I’m no great scholar or practitioner of Buddhism. I started attending dharma talks at a local Kagyu temple soon after I got pregnant for completely selfish reasons – I wanted to find more ways to deal with stress in my daily life. I felt more vulnerable than ever before. And I especially wanted hope for the future in the face of a war I did not support and a president I did not support (who had just been tipped to reelection by my home state). In the sangha, I found some people seeking the same.

Of that night of singing and the talk, what I remember learning best was that things like anger and stupidity can come through us in a neutral and benign way. It’s how we grab at or cling to them, the pentimento that we make of our experiences, that propels us to do hurtful things to ourselves or to others. And simply put, it’s a lot harder to cling to your past or your fears or your ego when you’re singing. (Or chanting prayers or mantras.)

A little over a year beyond that night, Declan’s hunger for language became overwhelming. He went from saying a few words to learning the name of every color, shape, animal and household item in his proximity as quickly as he could. One of his favorite words was “space.” He would jump up and down and cheer “space, space, SPACE!” in front of various Star Trek series’ openings, marveling at the planets, asteroids and stars.

Wondering if his interest would extend to science as well as science fiction, we started saving space documentaries on our DVR. Declan would watch them, and pick out and modify lines from the narrative to repeat over and over while he played, ate breakfast, tackled the dog or took a bath. His earliest mantras included the ominous-sounding “galaxies fade away, all stars merge” (from “Unfolding Universe“) and “just the right speed, just the right angle!” (from “If We Had No Moon“). Others were simpler, like the one he has most frequently yelled up the stairs at me while I try to get work done: “Saturn has rings, MOMMAY!”

There is such joy on his face when he says these things – an abandon in his mastery of language, in his strange desire to process the workings of the universe. And because of the vastness and mystery of his favorite subject, his mantras have a special depth and gravity (pun intended). Now that he’s a full sentences kind of guy, he still has a remarkable skill for picking up on soothing concepts, many of which still have to do with space. He also finds them in other places, like the latest wisdom from Blue’s Clues: “Stop. Breathe. Think.” A reminder he’s offered me three times today.

I’m still not very good at managing stress, and I am probably not any closer to being able to let anger and stupidity announce themselves without climbing on for the ride. But Declan’s mantras, like that night of singing, are often the things that remind me that forgetting myself and being in the moment are possible.

This is my 200th post!

Related Posts:

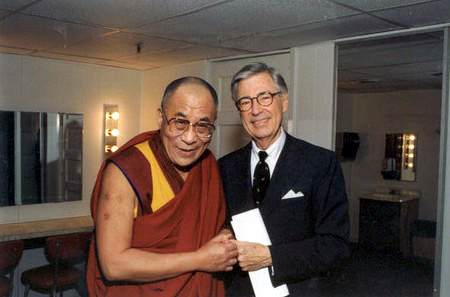

My son and I have been watching old episodes of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood lately. It’s much easier than I realized to get engrossed in the land of make-believe and film footage of the crayon factory as an adult. But it’s even easier to rest in Fred’s compassion.

My son and I have been watching old episodes of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood lately. It’s much easier than I realized to get engrossed in the land of make-believe and film footage of the crayon factory as an adult. But it’s even easier to rest in Fred’s compassion.